SELECTING BREEDING STOCK FOR HERITAGE HOGS

By: Mark Knauer, North Carolina State University and Alison Martin, The Livestock Conservancy

Selecting breeding stock for future generations is an important process to ensure herd productivity and profitability. In Heritage Breeds this involves two main aspects. One of these is assuring the integrity of the genetic structure of the breed. The second is considerations of productive potential. The following factsheet will outline important factors to consider when retaining replacement gilts and boars, emphasizing aspects of productive potential to be considered after the genetic value of individual animals for maintaining the breed has been determined. Selection criteria for the productive potential of breeding animals include: reproductive soundness, structural conformation, adaptive traits, growth rate and carcass characteristics.

Reproductive Soundness

Reproductive soundness, including all factors affecting an animal’s ability and willingness to reproduce, should be monitored at multiple ages for both boar and gilt replacements. Age at puberty varies among populations, and for some genetic populations can be less than 100 days of age. For most breeds, however, puberty would be expected to be later than 150 days of age. Separating males and females prior to puberty is critical to avoid unplanned matings and to avoid mating when gilts are too young.

Boars should be evaluated for mating behavior a couple months after they have reached a pubertal age, at least 7.5 months for many breeds; this age will vary for some breeds. Mating behavior can be determined by penning a boar with a gilt exhibiting the standing reflex and observing the boar’s libido and mounting behavior (NSIF, 2002). A boar with a good libido will seek out the female and attempt to mount her. Selecting a male with a high libido is especially important for herds where matings may not always be attended. This assures that boars will seek out the sows and mate them.

Gilts should be assessed for vulva and underline soundness at the time they are expected to be approaching puberty. For conventional breeds this would be 5-6 months of age, though it will vary among genetic populations. A gilt’s vulva should be well-developed (Figure 1). Small, infantile vulvas (Figure 2) should be avoided as they often indicate an underdeveloped reproductive tract that cannot function. At the same time, evaluate the underlines for teat spacing and quality. An example of a well-spaced, high quality underline is shown in Figure 3. Teats that are overly coarse (Figure 4) should be avoided as they may inhibit small piglets from suckling. Teats and underlines should be evaluated in both gilts and boars, because these characteristics are inherited, and the boar with weakness in these traits will pass those to his daughters. Teat number is also important, and varies breed to breed. The essential element is that teat number is sufficient for the anticipated litter size the gilt will be producing. To an extent, “more is better” is a good rule.

Once the basics of breeding potential are deemed acceptable, actual breeding behavior and success can be evaluated. The wise farmer will keep records of matings to learn which gilts are successfully bred, and whether a boar is successful in impregnating sows and gilts. In herds where replacement rates are low, longevity may be key for capitalizing on the most productive years of a sow’s life, after third parity. Following a trial period, unsuccessful breeding animals should be culled from the herd in order to reduce unneeded use of resources.

The last element of reproductive soundness is litter evaluation. Selecting breeding stock that consistently give birth to and wean large, healthy, productive litters is the secret to herd improvement. There may be instances where maintaining the genetic diversity represented in a pig or litter means that animals are maintained despite low productivity. In this case, the goal should always be to correct the weaknesses in the next generation by using these animals carefully and mating them wisely.

Structural Conformation

Structural conformation should be evaluated on all potential herd replacements. Learn to identify the expected conformation of the breed you are raising, and study the breed standard. Some structural defects impact soundness and breeding, and animals with such defects should be culled from the breeding population. Evaluate structural soundness at several times as animals grow, for example, at weaning, at 6 months, and prior to breeding. Conformation should be balanced, that is, head, neck, body, and legs should be uniform and symmetrical on the left and right. Examine each pig from the top, front and rear. The spine should be straight, as should be the legs when seen from the front and rear. Proper feet and leg structure in both sexes is especially important in natural mating settings. Emphasis should be placed on the side view of the front legs (Figure 5), because the conformation revealed in this view relates to mobility and the longevity of physical soundness. Weak pasterns seem to be tolerable, but weak knees need to be avoided because such pigs break down earlier than those with sound conformation. Pigs that are buck-kneed can further be identified as they generally have smaller front toes and take shorter strides on their front legs. Boars with buck-knees have more difficulty with mating, and both sexes have greater difficultly rising to a standing position as they mature. As a result, buck-kneed pigs should be culled unless absolutely necessary for maintaining genetic diversity. When evaluating rear leg conformation, pigs that are post-legged (Figure 6) should almost always be culled, because this conformation leads to early structural problems, lameness, and a shortened productive life. Tail set is another trait that affects breeding ability. If tail set is too low it can impede breeding and birth.

For heritage breeds, considerations to preserve genetic diversity may occasionally require using an animal that has weak conformation, because it represents a very rare bloodline. In this case, all consideration should be made to match the animal with mates who are very strong in the conformational area where the rare bloodline is weak.

Adaptation

Many niche pig producers decide to raise heritage breeds because of their adaptive traits, and these should play an important role in selection of breeding stock. Close observation of behavior and good record keeping are important in deciding which animals to keep and which to cull. Depending on the current state of the breed and the objectives of the breeding program, animals may be selected for mothering ability, litter size, temperament, foraging behavior, disease resistance, longevity/length of productive life, and adaptation to the environment. Individuals that do not meet farm criteria for these traits should be culled. Sons and daughters of individuals who are superior in these traits are favored when deciding on replacement breeding stock.

Growth Rate

Perhaps the most basic trait to evaluate is growth rate. Pigs that grow faster require fewer days to market, and inferior growth can be an indicator of poor reproductive health. Good record keeping is the key to improving growth in the herd. Size differences among littermates can be distinguished by visual inspection, or with a scale, and the results should be recorded and tracked as the animals grow. Weight is commonly measured prior to or at weaning, and then again at market age. Unless a farm scale is available (Figure 7), farmers may have weights only on pigs that are processed. Alternatively, a hog weight tape can be used to measure heart girth circumference (Figure 8). By tracking the growth rate of the offspring of each sow and boar, farmers can select replacement gilts and boars from the families with the best productivity.

Selection should not be based on growth alone, but balanced against adaptive traits. Growth rate differences between litters can be highly influenced by environmental effects. One way to balance this is to compare each piglet to its littermates, selecting the best of the litter rather than selecting across litters that might have had different numbers, ages of dams, and other factors that influence growth rates. Hence farmers should consider selecting for growth rate within litters, always keeping the best performers from each litter as breeding stock. This practice also helps assure accumulation of inbreeding is reduced by maintaining as much genetic diversity as possible.

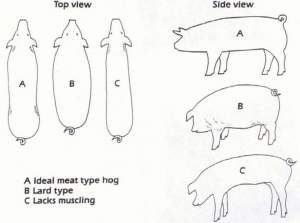

Carcass characteristics (i.e. backfat and muscling) can be estimated visually, or objectively by using ultrasound technology. The latter provides more precise assessment of leanness and muscling, but adds considerable expense. If it is available locally, work with the ultrasound technology provider in using the data in selection decisions. Ideal carcass characteristics for a farm may vary depending on the target market and for the breed. For example, a breeding objective for pigs that are very feed efficient would require selection for lean, meat type animals. Yet, heritage breeds originate from a time when the market valued more marbling and lard, so the farmer must be familiar with the ideal body type for their breed.

Visual appraisal of carcass traits should occur near the desired market weight. Figure 9 depicts sketches of a pig of lean body type, (A), a lard-type pig, (B) and a lean pig with inferior muscling (C). Although heritage breeds have more fat than modern lean breeds, excessive fatness is not desirable and affects health and reproduction. Breeds that are especially prone to obesity, such as Guinea Hog and Ossabaw Island, should be monitored and their feed intake adjusted to prevent obesity. Some breeders may wish to select breeding stock less prone to fattening, so long as they do not deviate too far from the expected conformation for the breed.

In a visual assessment for carcass characteristics, the farmer will evaluate the breadth (side to side), length (fore to aft) and depth (top to bottom) at various points of the animal against the body type for the breed or bloodline and compared to other animals in the herd. Standard points of evaluation for visual assessment include: breadth of the head and neck, uniform breadth of the back all the way through the hindquarters, body depth at the shoulder just behind the arm (heart girth), length of the body, and fullness of muscling in the shoulder, body, and hams. Pigs chosen for breeding should be medium boned, sufficient to carry their weight, but not heavy boned, as that reduces yield. An overall impression of harmonious and strong conformation nearly always accompanies animals with good production records.

Summary of Key Considerations for selecting breeding stock:

- Reproductive soundness

- Good libido and mating behavior

- Well-developed vulva

- Well-spaced underline with high quality teats of appropriate number

- Breeding behavior

- Fertility

- Litter size and health

- Longevity

- Structural conformation

- Top, front, and rear view – straight and balanced

- Front leg side view – normal or weak pasterns favorable

- Rear leg side view – consider culling post-legged animals

- Tail set

- Adaptation

- Health

- Mothering ability

- Temperament

- Foraging ability

- Adaptation to local climate and weather

- Growth rate

- Body weight or heart girth

- Rate of growth from weaning to market weight

- Consider growth within but not between litters

- Balance selection for growth with genetic variability and selection for adaptive traits

- Carcass characteristics

- Ideal may vary depending on your breed and target market

- Breadth, depth, length and muscling can be estimated visually

Figure 1. A gilt with a well-developed vulva. (Photo courtesy of National Hog Farmer)

Figure 2. A gilt with an infantile vulva. This gilt should be culled. (Photo courtesy of National Hog Farmer)

Figure 3. A gilt with well-spaced, high quality teats. (Photo courtesy of National Hog Farmer)

Figure 4. Small piglets may have challenges nursing the coarse rear teats on this gilt. (Photo courtesy of National Hog Farmer)

Figure 5. Side view of the front leg for normal (left), weak pasterns (middle) and buck-kneed (right). Buck-kneed pigs should be culled. (Photos courtesy of National Hog Farmer)

Figure 6. Side view of the rear leg for a normal pig (left) and one that is post-legged (right). Post-legged pigs should be considered for culling. (Photos courtesy of National Hog Farmer)

Figure 7. A farm scale suitable for weighing pigs

Figure 8. Pig weight can be estimated using a hog weigh tape to measure heart girth circumference.

Figure 9. Examples of a lean pig of modern meat type (A), a lard type heritage pig (B), and a lean pig with inferior muscling (C).

References:

Application of Selection Concepts for Swine Genetic Improvement. https://swine.extension.org/category/breeding-and-genetics/